This year’s forecast: Sunny with a chance of solar storms. As the sun enters a “solar maximum” phase, an active period that it enters every 11 years, space weather is a hot topic.

Meteorologists can tell us if it’s going to rain or snow, but their knowledge base is largely limited to below the stratosphere. Space weather researchers examine variations in the space environment around the Earth, extending from the sun to the upper layers of our atmosphere.

Solar storms, or bursts of electromagnetic energy, can send shockwaves through the solar system. They can cause stunning lower-than-usual aurora borealis but can also wreak havoc on staples of modern life, including satellites, cell phone service, the internet, and GPS. Back in 2003, the northern lights reached as far south as Australia, astronauts in the International Space Station took cover, and communication problems disrupted commercial flight operations.

The sun continuously emits energy, so there’s always another event of varying intensity on the horizon. That we seldom notice a solar storm underway is thanks in large part to researchers and innovators focused on space weather.

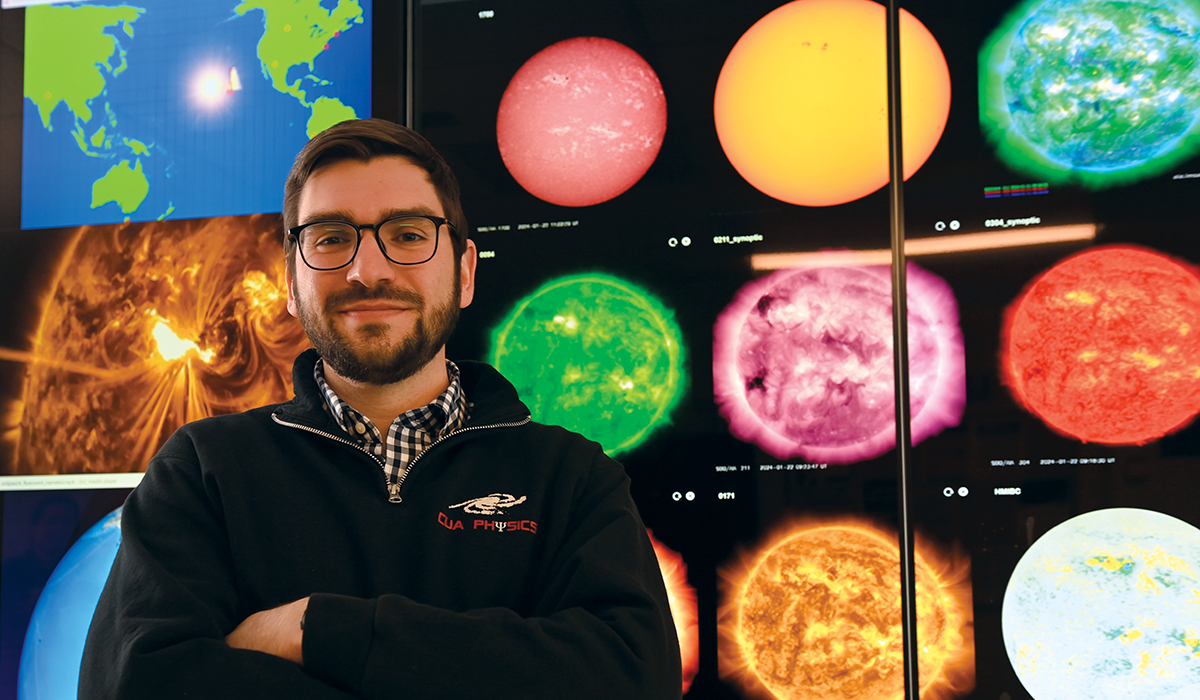

The Catholic University of America is a leading institution at one of the largest, if not the largest, hubs for heliophysics research in the world. In 2021, the University received $64.1 million — the largest grant in University history — from NASA to lead PHaSER (Partnership for Heliophysics and Space Environment Research). This cooperative agreement with five other higher education institutions supports the agency’s heliophysics division at Goddard Space Flight Center, one of NASA’s major centers for space science and exploration in nearby Greenbelt, Maryland.

About 100 space weather scientists who drive discovery in the division are University employees — and this number doesn’t include researchers in PHaSER’s sister cooperative CREST II (Center for Research and Exploration in Space Science) and many other alumni who work at Goddard.

Physics Research Professor Robert Robinson, who leads PHaSER as its principal investigator, explained the rise in visibility of space weather has to do with society’s increasing reliance on technologies, especially in communications, which are sensitive to solar events.

He said interest is “blossoming,” especially among the next generation. Space weather is an emerging and evolving field, offering ample opportunities to boldly go where no researcher has gone before.

“Young people and students are excited to make a difference and be pioneers,” he said.